The heart of the horse part 2

| July 3, 2023 | Posted by Melinda under Uncategorized |

Find Part 1 here

Turns out that the bots really hate <3 in the title…so my cutesy “The <3 of the horse” didn’t show up in part 1, so I guess I’lll dump the cutesy emoticon title and just use words. sigh.

Why should you spend the money to get a cardio consult and go beyond the stethoscope?

Does having more information about this actually matter?

It’s a valid question.

Not every little heart defect in the horse something means something. Horses are incredible athletes and a little bit of “slop”often isn’t a big deal. It’s very possible that you show up at your cardio consult and are told that you and your equine partner are just fine to continue your riding adventures with the mildly leaky pipes and pump.

But yes, you really do need to go to the cardio consult because assuming it’s something benign could get you or someone else handling or riding the horse killed. It could mean an increased risk of a “sudden cardiac event” turning your horse into a 1,000-pound squisher of humans.

Applejacks (Or maybe it was Applecakes? That’s the problem with made-up names. I can’t quite remember what I decided to call the old mare that was the inspiration for this post) with her “lub-dub *whoosh* lib-dub *whoosh*” murmur definitely needed further work to see whether continuing to have her perform under saddle was safe.

Cardio consult: Echocardiogram

The echo confirmed that Applesnacks had an aortic regurgitation, common in older athletic horses who continue to go on doing their jobs. The valve between the heart and the big blood vessel that leaves the heart, called the aorta, can have degenerative changes (like a door that’s gotten slammed too often) as the horse gets older. Eventually it doesn’t shut all the way and allows blood to escape backwards under pressure, which we can hear with the stethoscope.

This by itself isn’t a big deal, but over time blood whooshing backwards where it shouldn’t can cause the heart to become stretched (it’s just muscle after all!).

Why is a stretched out heart a big deal?

Because the heart relies on electrical signals from cells that are in the wall of the heart to tell it to contract, and it also relies on its mechanical muscle cells to do the contracting. Contracting is important because that’s how the heart accomplishes its purpose of pushing and pumping blood throughout the body. Blood = nutrients. Blood = oxygen to organs like your brain that need fresh up to date oxygen every minute to remain conscious. Blood = removal of waste products that can kill you. Blood pressure = fluid balance in your body that you depend on for survival.

When the wall of the heart abnormally stretched because of abnormal flow of blood two things can happen.

The first is that the electrical highway system in the heart is disrupted. This can cause fatal arrhythmias – which can cause that “acute cardiac crisis” (such a nice name for a sudden go-squish and thud moment) situation I mentioned in the first post.

The second effect is that the heart isn’t able to squeeze to pump well. Just like a worn-out stretched balloon, or saggy baggy stretched out skin…when the fibers are stretched or thinned it’s more difficult to squeeze together smartly and move blood. A heart that is a poor pump can result in congestive heart failure. This causes medical and performance issues and eventual death as all the things blood flow is responsible for (nutrient delivery, oxygen, waste product removal, and fluid balance) start to stutter.

But, none of these things are not inevitable! Horse hearts are amazing and just because you have a little backwards flow at a value and can hear a mumur with your stethoscope doesn’t mean the heart is so fragile that it gets all bent out of shape immediately. This is why you need further testing! It. Could. Be. Fine.

Key point: We can hear the murmur using a stethoscope, but there’s no way of being able to measure whether the heart is abnormally stretched without using an ultrasound to look visually at the heart.

Reminder of Key point from Part 1: Without knowing what the heart looks like, we can’t tell you what the murmur means or “how bad” it is (unless the horse is already showing signs of heart failure. In which case we can go ahead and assume generally “not good” but still can’t tell you specifics. Still waiting on that crystal ball that is on backorder etc.)

Bottom Line

So the workup in these cases generally looks like this:

1. Found murmur, do an echo.

2. If heart looks fine, the horse is acting fine, and murmur is one of those benign ones, perhaps you take an off ramp here and monitor murmur and echo on some frequency for changes.

3. If the heart shows some structure changes, or to be extra safe because of “circumstances” around the horse and its job, do an exercise ECG to make sure it is not throwing arrythmias.

4. If arrhythmias are found do not pass go, do not collect $200. Reconsider everything you are doing with the horse. If everything looks A-OK, proceed with life and keep an eye on things at some frequency.

Real-Life is Messy

This seems straightforward and most of the time cases do follow this road map. But life can be messy. I’m going to share with you the rest of the story of Applepie because it’s an example of how real-life can be more complicated than our nice text book algorithms.

As you recall it was confirmed that she had an aortic murmur. Common in older performance horses, which she *was.

*note the continued use of past tense. This should be a warning shot of what kind of case this ended up being.

Applesnack’s case was a little unusual from the beginning. Vets always say that sound and intensity doesn’t correlate well to how “bad” a murmur is and whether the horse is still rideable, but AppleLick’s murmur sounded a little weird, it was LOUD, and it reverberated throughout her ENTIRE CHEST. The wild thing was we didn’t even know she HAD a heart murmur until she had a different medical problem and had a physical exam. She was treated for the infection she initially presented for, and a recommendation was made to stop riding her until an echo could be done.

On ultrasound/echo her aortic valve didn’t just have the normal degenerative change that we would expect in a “normal” old horse with an aortic regurgitation murmur….the valve actually looked like at some point it had been TORN IN HALF. You’all, horses are amazing. The valve was sort of functioning, but there was an extra flap and lots of extra flow backwards through the valve.

On echo and physical exam she did not show signs of heart failure (yay!). But, she DID show signs of heart enlargement (booo!). It was very mild, but it was there.

Remember that enlargement of her heart chambers means that she is at risk for abnormal electrical activity. This can lead to things like *A-fib and VPCs (other things too. But let’s focus on the things that will kill her and squishy humans). A-fib is bad. VPCs are also bad.

*uncoordinated, rapid rhythm of contracting. Not very effective at moving blood around the body and to critical things like their walnut-sized brain which is responsible for keeping them upright and on their feet.

To clear her for use, she needed an exercise ECG. Which was going to be a PITA in multiple ways in this case. Basically you have to make the horse perform at the desired level (her job required her to go very fast, which she did very well and insisted on doing to the best of her ability. Testing her at speed was going to be…interesting) and then hook ECG’s up to her and monitor for abnormal electrical activity.

The brief ECG that we do at the time of the echo didn’t show anything other than a 2nd degree atria-ventricular block (see part 1). But, let me tell you she was not a fan for the ECG part of the echo exam and she tried to murderate us until we decided to discontinue that part of the test and sedate her as well. Getting a useful exercise ECG out of her was going to be…challenging.

Although her murmur and her heart status would be considered moderate to severe it was the off-record opinion of most of the vets involved that she was probably not throwing arrhythmias right now (the thing that would make her drop over dead with or without a rider), she hadn’t shown any sign of exercise intolerance or issues over the past several years. If the ECG confirmed this, she could continue to be used and repeat monitoring echo and ECG would need to be done at some frequency (probably every 6-12 months).

Seems like a slam dunk. Pay the money, confirm she’s safe to ride, and continue merrily on our way.

But, like most older horses she had more than one issue.

Welcome to the art of medicine.

We found the murmur because she got sick with an *infection. Antibiotics will help, but to resolve it surgery is needed. The cost of surgery is not prohibitive and it generally carries a good prognosis for return to use (this is a question you should always be asking your vets!).

*I’m being deliberately vague because I don’t own this horse and I have permission to share generalities only.

Here’s the problem.

Now we have two issues. Both of which on their own carry a good-ish prognosis.

But together….they complicate each other.

Let’s recap.

We have a horse who has a performance job. She needs surgery to treat an infection and also has a RAGING heart murmur that shows some cardiac changes.

Did I mention she’s in her 20’s?

There’s a double whammy to this too.

Horse with murmurs and abnormal valves are more prone to endocarditis – ie infection of the heart valves.

The infection that is present could be making the heart worse.

The heart problem makes surgery to address the infection more risky.

Surgery is needed to address the infection because even with systemic antibiotics, she’s still ill.

We went from having two separate problems that each carry a favorable prognosis, that together make the clinical picture very complicated. And now we are damned if we do and damned if we don’t.

In a world with unlimited money you do the surgery, and if she survives (including almost daily sedation that will be needed for the after care due to her temperament – which is also risky with the heart problem. AND she doesn’t develop some other complication like colitis from the antibiotics), you repeat the echo and hope that it looks the same as it does now, then do the exercise ECG and cross your fingers that there are no arrhythmias and she can go back to her job. Then, you recheck the ECG and echo every 6 months and hope that everything remains stable for at least a couple more years (because remember, she’s in her 20’s after all) and nothing else pops up, or her mild osteoarthritis doesn’t get worse and force retirement.

That’s a lot of crossing fingers and hope for the amount of money we are talking about. This plan isn’t wrong, and it’s absolutely what I would make sure clients knew what was available to them.

But. Here’s where I’m a pragmatic.

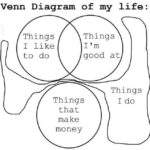

Would I personally spend that kind of money for a prognosis that is at best guarded to poor? Pretending that this is Farley, what would I do?

It’s not wrong to choose the gold-standard plan if it’s available to you. I wouldn’t do it for Farley. Assuming she was still competing in 100 milers, I wouldn’t spend that kind of money, and put her through that kind of stress and discomfort to eke out a few more competitions. I also wouldn’t do it to give her a few more years on pasture. Would I share my sentiments in a clinical setting with a client? Probably not. Because this comes down to a lot of “feelings” that are very personal for specific circumstances and how people look at life and death.

In the end, the clients who owned Appletree decided that based on all the information available, surgery was not an option. An exercise ECG was considered but combined with the infection, none of us felt good about continuing to ask her to do her job, especially because weeks of antibiotics still hadn’t gotten her comfortable and feeling good.

In the end, despite having pasture retirement options available and desperately wanting that for her as a thank you for her years of service, she could not be made well enough to turn out to pasture without the risk of a bad end and suffering, so the difficult decision was made to euthanize her. (See the post The Good Death if you need help understanding this decision).

Sometimes life sucks.

———————————————————————

If you are reading this post because you found me on google after trying to make your own decisions about a heart murmur your vet has heard on your horse, I hope that it’s one of the simple cases. But if it isn’t, you aren’t alone (and I’m sorry). Medicine is more than the neat concise paragraphs in my textbooks with their treatment plans and procedures. As you work through a difficult case ask yourself:

- What is the return-to-use prognosis?

- What is the prognosis for general survival and what does that look like (ie pasture turn out? or small paddock with more intensive care? What special needs?)

- What co-morbidities are there, and how might they impact the case?

- Can the cost for the treatments be spent without resentment or regret if the outcome is poor?

- Does having more information change the treatment plan? Or needed for the safety of the humans involved? (if so, strongly consider spending the money on diagnostics!)

These questions are useful for any major medical decision, not just heart cases. Just like the questions I asked in the Good Death post, thinking through some of these no-easy-answer questions for medical treatment can help prepare you for working through them when you don’t have the luxury of time and now they aren’t theoretical. Best of luck <3.