Recovery Thoughts II

| February 26, 2014 | Posted by Melinda under Uncategorized |

I summarized yesterday’s post with the statement: The major consequences of stress/stimulus applied during a run is muscle damage, fuel depletion, and psychological/emotional stress. In order to fully utilize them again, you need to repair or refill them to capacity.

Tomorrow we are going to add a caveat to that statement: “….You need to repair or or refill them to capacity before you can fully utilize the again – but sometimes you don’t want to“. Sometimes you don’t WANT to wait until you have fully recovered , or order to get additional training benefits for your next event.

But, before we can talk about not recovering, we have to take a look at what constitutes a complete recovery.

Bouncing back

The amount of time it takes for an athlete to “bounce” back from a work out depends on how large the stress was for the athlete. This depends on the WORKOUT but it also depends on the INDIVIDUAL. Different horses/people have different abilities to bounce back after a certain type of work out.

Here’s a running example.

In general, there are 4 types of runs that are in my running program: interval/HIIT, Long, Tempo, Race.

Note: I’m ignoring my “easy” runs because by definition those runs are just to keep me moving an sane and I am NOT trying to apply any sort of stimulus or adaptation during those runs.

Each type of run has it’s particular challenges whether it’s muscle damage, fuel depletion, or the mental component. The exact combination of stress for each athlete for each particular workout is different! Recovery time isn’t a static concept – I do NOT recover particularly well from tempo runs. However I bounce back very quickly from HIIT type running. You may be completely different.

I believe horses are the same way. Some horses are more drained by long easy rides. Others by shorter faster interval rides. Maybe certain types of terrain take more out of certain horses. It’s certainly helpful to have guidelines such as “4 weeks after a 50” or “6-8 weeks after a 100” as guidelines for recovery after endurance rides, but it all depends on how stressful the particular ride was for the horse. My instinct (just opinion here!) is that successful endurance horses are those that the stress of competition+long miles is a “type” of workout they bounce back from relatively easily. Either because of training, or intrinsic personality. Physically Farley bounces back from long miles really well. Psychologically I feel like Farley doesn’t handle conditioning as well as she handle’s the stress of an actual event. ie – the mental stress of long conditioning without the interest other horses and vet checks and camping is harder for her to bounce back from, than if we were at an actual event.

Objective measurement of recovery

Back on the human side of things, Magness has a nifty chart that divides recovery assessment into 4 categories.

1. Emotional/Mental Readiness

2. Stress response

3. Physical Damage

4. Neural/Central Fatigue

For each category there is a couple of different ways to assess how recovered the athlete is. They range from questionaires, to physiological parameters, to fancy tests.

The nifty thing is that for each category there was one simple test that I thought “I could do that!”.

Emotional/Mental Readiness

For the emotional/mental readiness category there a questionaire etc. I decided I didn’t need to take a test to see how I felt. HOWEVER, recognizing this as a specific category in the recovery assessment means I need to take my emotional response to a stimulus seriously. For example, if my gut reaction to doing Tevis right now makes me sick to my stomach in a bad way and not an excited way, then I’m still in the process of recovering from my last Tevis and I’m not ready to go there again. Validating those feelings and recognizing that they are a component of the recovery process (and future conditioning and training process) is a major change for me.

In some situations I need almost no recovery in this area. After I finished the 35K on Saturday, mentally I was immediately ready to go back out again. Very very little of my “psychology” component was depleted in that run and as a result almost no recovery was needed in that category.

This category is hard to evaluate in our horses. I think judging their readiness to work is very subjective – and ever since I saw the results of a study where they let horses decide whether to work, go stand in a paddock, go to a stall, go to a pasture etc – I’ve decided that humans are probably not a good judge of knowing what a horse wants. Over time as I develop a relationship with a horse I would like to think it’s a partnership of similar goals and aspirations – but I also know that habit, training, personality of the horse etc. can muddy the waters when deciding what our horses want and what they are ready for. Until I learn to talk horse, I just do my best to evaluate my horse’s attitude after a hard workout or event against what is “normal” for her and respect that as part of her “emotional” recovery.

Stress Response

Amid the fancy tests I was happy to see the good ole’ heart rate variability test here. I’ve gotten out of the habit of taking heart rate in the mornings before getting out of bed – but I used to do it on a regular basis. It really is quite consistent. Subjectively I find that I get out of breath faster and my heart beats a little faster the first few days after a really hard event. But I’ve never thought to take a resting pusle, so objectively I have no idea. My normal resting heart rate is 56-60 bpm and I’m going to keep an eye on it the next couple of months and see if it correlates well as part of the recovery process.

It is my guess (no science here beyond my opinion folks!) that using HR to assess stress recovery works in horses. If Farley’s heart rate is running a bit high at rest, or tends to run higher as we do something than normal, she probably isn’t recovered from the previous workout effort.

Physical Damage

Like the stress response/HR I was happy to see the simple test of “muscle soreness” here. A couple of years ago (has it really been that long?) I decided I would no longer run through muscle soreness on a regular basis. I think that simple change has dramatically changed how well I recover and fast I recover. I saw an article in the NY times health and wellness blog written by Gretchen Reynolds this morning that discussed doing HIIT training a few times a week or more often (6x a week). The athletes doing the training more often did NOT get the same benefits of the training as the group doing it less often until they backed off the frequency and let their bodies recover between workouts.

If I evaluate how well I assess my personal recoveries during workouts, physical damage is probably where I do the best – emotional/mental readiness is probably where I do the worst……

Neural/Central Fatigue

If you aren’t familiar with the concept of central fatigue and don’t own the Science of Running Book, I recommend that you go over to Magness’s blog and take a look at this Post.

In my training logs, if I did an easy run after a recent hard interval run I might put a comment about not being sore or tired, but not having any “bounce”. My feet sorta of feel glued to the ground even though the stride length and turnover might be identical.

Turns out there’s an actual name for that phenomenon and its a component of neural/central fatigue.

And it’s not all mixed up with muscle soreness and damage either like I thought…it is its own seperate thing! And it may recover at a seperate rate than the muscle damage, and may occur without muscle damage.

One of the ways that neural/central fatigue can manifest is increased ground contact time in a stride.

One of the ways of listed of assessing recovery of central fatigue is the “finger tap test”.

I wasn’t familiar with the test, but it sounded like a rather simple physiological test – like HR or muscle soreness – and so I did a little research and it turns out it’s a very simple concept – with your palm on the table you tap your fingers as fast as you can for a certain period of time and count the taps. A tap count that is significantly below your median/mode means that you aren’t fully recovered, a tap count significantly above means you might get more of an extra hard work out that day (go ahead and add those extra intervals!).

The idea of trying to count the number of taps seemed a bit daunting and so I was pleased to find an app (of course right!) that will do it for you. It was cheap and being a person that am always interested in more numbers and simple tests, I bought it. It will be awhile before I have enough data to see what my averge tap is and be able to use it as a training tool, but I think it will be interesting.

What about our horses? I wonder whether the increased ground contact time during the stride is an indicator of central fatigue. I notice this in my own horse, and in other horses as they go through a ride. Gradually they get less bouncy as they go through the vet checks. The increase in ground contact time (less bounce) doesn’t seem to be related to muscle soreness or delayed heart rate recoveries. Magness says in the Science of Running book that “fatigue is largely related to mental fatigue and stress.” I find this true of myself – when I say I am “so tired” and “fatigued”, it’s usually a mental state that is causing physical symptoms, rarely the other way around. On my long runs it’s rarely my muscles or something physical that makes me fatigued – it’s the concentration and mental game of having to be “on” for so many hours.

Maybe that’s why some horses retain their “bounce” throughout a ride – maybe those are the horses that are battling the least amount of “central fatigue”. That isn’t to say that muscle damage, emotional stress etc aren’t necessarily occuring – just that for that particular horse athlete in that particular type of event, may not be dealing with the particular stress of central fatigue.

So what do I do with this information?

Realizing the nuances of recovery has already prompted me to make several changes in how I assess my readiness for my next workout, and how I schedule my training runs.

1. I’m taking a CNS tap test prior to each run. I’m recording the number. Because I don’t run every day, I’m also doing a tap test each morning so I can establish some sort of average for myself. At some point I’ll be able to see whether before some runs I have a higher or lower tap test and use it as an indicator of whether I could use another rest day, or if I go with my plan, or if it’s a day I should push myself. You might ask what the big deal is – if I feel good go for it – and if I don’t, take it easy. The problem is that being able to accomplish a run also affects the emotional/phsycological component of the running. Having an expectation of being able to finish a run and not being able to do so is a disappointment. Not allowing good recovery in ALL aspects – not just muscle soreness.

2. I’m taking a morning heart rate. So I can have a normal baseline, so that next time I do an hard work out I can see whether it changes in the days afterwards – and to see how significantly life stress (like being in clinics) may be changing my ability to handle a hard work out.

3. I’m listening to the emotional gut reaction I have to certain workouts – where before I would ignore as not important. (and I’ll be training this component – but more on that in next post).

4. I’ve acknowledged that my different training runs are hard in different ways, and may require different types and lengths of recoveries. And that my need for recovery after a certain type of run may differ from a standard program, or my friend’s recovery. For example – I find tempo runs really really emotionally stressful, AND result in more neural fatigue. Races are emotionally stimulating, but require prolonged muscle damage healing time and usually have increased central fatigue associated. Beyond some occasional muscle soreness, I bounce back the fastest from HIIT/interval runs. I can schedule more of those.

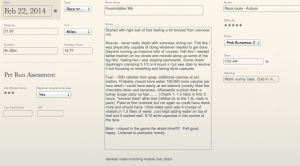

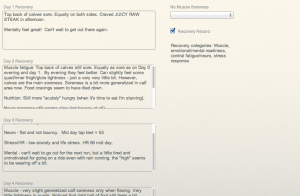

5. I’ve changed my training logs to track some of these additional parameters. I’ve added a “pre run assessment” of what the am HR was, the prerun tap test and whether I’m running through any muscle soreness. I’ve also added a “recovery log” where I evaluate how I’m recovering from a particularly hard run in the 4 categories (emotional, muscle, central fatigue, stress response). I won’t do a recovery log for each run – only those runs that were significant mile stones or significant runs in some way (races, mile stone runs like mile tests or when I change a HIIT pattern etc.). I’m going to assess runs in terms of psychological, fuel, and muscle (not just focusing on what was sore, or hurt).

You can see that some of the fields are blank because I added them AFTER I did this run, or the record (like the recovery record) is still in progress.

Sometimes you don’t know how the data will come in handy – but especially when it comes to running or endurance, it’s hard to go back and figure out exactly what worked and didn’t the last time you did something big (like a 100 or tevis or a marathon). I try to make it as easy as possible to enter the data so I will record stuff. If I find I wish I had some piece of information, I add it to the data base and assess it going forward.

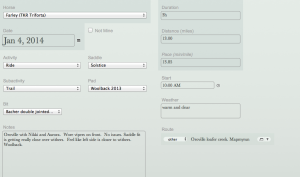

As another example, here’s a screen shot from Farley’s database.

Wrap up

So far we have talked about why we need recovery and some ways to assess recovery. And now, because I’m finding way too much to ramble on about the subject, we again are going to have to pause in the conversation and continue this topic tomorrow. Tomorrow’s focus will be on how to use our recovery to our advantage in a conditioning program.

By the way if anyone uses the mac database program bento I would be more than happy to share my template that I developed for running and riding logs