Splints, the boring part

| October 23, 2014 | Posted by Melinda under Equine Endurance, Vet & Sports Medicine |

While I think this post covered splints well enough, it was suggested that perhaps I should provide some sort of reference that went beyond pre-schoolers, paste, miniature dump trucks, and anti-social suspensories.

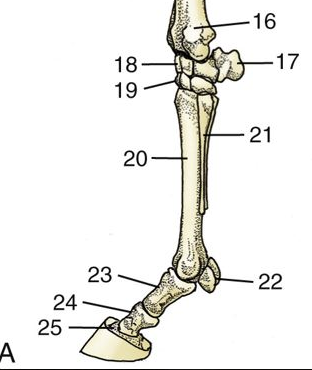

The splint bones live on either side of the canon bone on all 4 legs and are properly called the metacarpals II and IV, or alternatively the maratarsals II and IV on the hind legs. I’m going to keep calling them splint bones if you don’t mind.

Image from Dyce’s Textbook of Veterinary Anatomy. The splint bones are labeled as “10” in this image. The end as little “buttons” or bumps at the end.

The thing that holds the little splint bones to the cannon bone is not actually paste applied by a pre-schooler but fibrous tissue. The fibrous tissue can/will ossify and this is can/will cause inflammation and pain. This is the process commonly referred to as “splints”.

The other thing that can happen is that the bottom part of the splint bone can break off. The upper portion is adhered tightly with the fibrous tissue, but the bottom part isn’t firmly attached to the cannon bone. In my vet textbook, they state that when it fractures “it is a simple matter to remove the fragment below the fracture line”.

Simple right? Ummm….somehow the textbooks don’t tap into the pure anguish that occurs when your horse’s leg blows up and they are lame because of the inflammation of the fibrous tissue that got irritated. Or even worse a FRACTURE.

And it isn’t always complication-free or straightforward.

The problem is, that there are lots of important structures in that area that could get pissed off if the splint bone is pissed off, or heaven forbid, in pieces.

Like the suspensory (which is also called the interosseous).

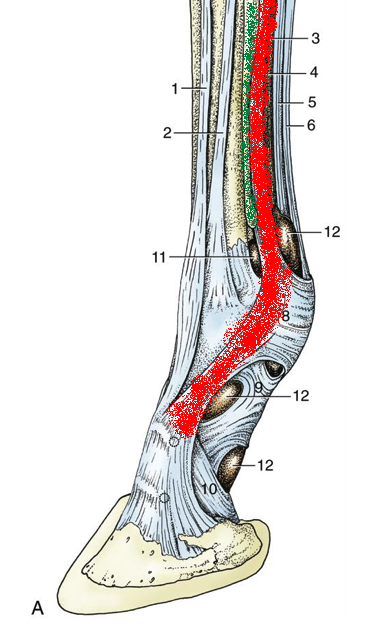

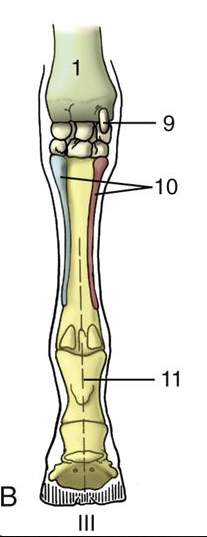

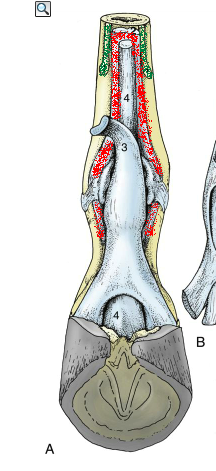

In these images the green structure(s) is/are the splints and the red is the suspensory. Remember that the suspensory runs underneath the deep digital flexor and branches at some point

When a bone is inflamed or damage or injured, it tries to repair itself. I’ve covered those processes (which are similar to the way bone adapts to conditioning) in earlier posts here and here.

Bone responds to the forces of physics and remodels and adapts with the goal of stabilization and strength.

The problem with those two goals is that they are often accomplished with a lot of extra bone material.

As you can probably guess from the highly artistic drawings…there isn’t a lot of room for extra crap around the splint bones….

In fact, it’s a 2 way street. According to my radiology reference (Textbook of Veterinary Diagnostic Radiology), pathology in the suspensory can actually change how the splints look on radiographs.

In summary….splints can be minor. A little bit of remodeling. A little extra “paste” to re-stabilize a pissed off splint bone. OR, they can be a big deal as the first the inflammation pisses off surrounding structures, with the final insult being gobs of new bone remodeling that interferes with the suspensory.

Splints don’t always occur because the horse was ridden too hard, too fast, or with too many miles. It can be an imbalance in the leg (hoof or other conformation flaw), trauma from trail debris or an interfering hoof, or a pasture accident.

I’ve had good luck with splints over the years. The worst was a hind leg splint that I *think* happened when Farley kicked the pipe corral fencing she lives in. It was the most swollen and took the longest to resolve (~10 days). The rest were relatively minor, resolved without issue or treatment beyond a couple days off. However, not all splints are benign and playing the “guess the outcome” game is not fun.

See, told you the comic covered it.

Questions?